Irfan Habib

Born: 12th August 1931, Baroda (Vadodra) in Gujrat India.

Father: Prof. Mohd. Habib (A noted historian and Alig)

Mother: Sohaila Tayabji (Grand daughter of Justice Badruddin Tayabji of Bombay)

Children:

Education:

1951: B.A. AMU Aligarh with First Position

1953: M.A. (History), AMU Aligarh with First Position.

1956: D.Phil. from New College, Oxford.

Career:

1953: Lecturer, Department of History, AMU Aligarh

1960: Reader, Department of History, AMU Aligarh

1968: Jawaharlal Nehru Fellow.

1969: Professor, Department of History, AMU Aligarh

(Retired on 30.08.1991)

1952: Editor, Aligarh Magazine (English)

1982: Watumull Prize of American Historical Association.

(Jointly with Tapan Raychaudhuri)

1975-77 &1984-88: Chairman, Department of History, AMU Aligarh

(14th June, 1984 to May 1988)

1975-77 & 1984-96: Coordinator, Center of Advance Studies (CAS), Department

of History, AMU Aligarh. (14th June 1994 to 13th May 1996).

: Dean, Faculty of Social Science

1986-90: Chairman, Indian Council of Historical Research New Delhi, India

(9th September, 1986 to 1st July 1990)

1981: President, Indian History Congress.

1997: Elected Corresponding Fellow, British Royal Historical Society.

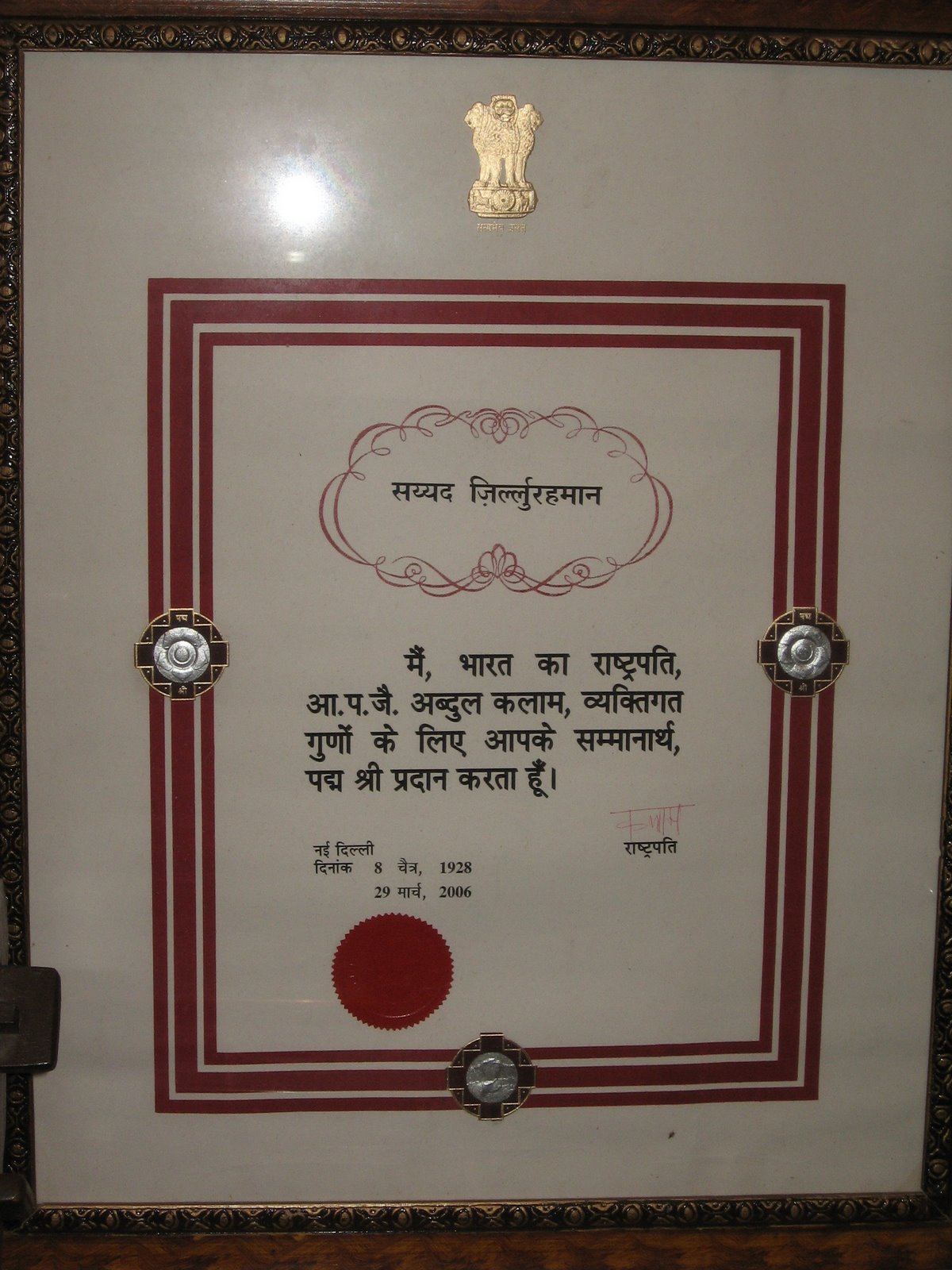

2005: Padma Bhushan, Government of India

2006: Muzaffar Ahmad Memorial Prize

2006: Vice-President, Indian History Congress.

2007: Professor Emeritus in Dept. of History AMU Aligarh

Selected publications:

Books Authored:

- The Agrarian System of Mughal India 1556-1707. First published in 1963 by Asia Publishing House. Second, extensively revised, edition published in 1999 by Oxford University Press.

- An Atlas of the Mughal Empire: Political and Economic Maps With Detailed Notes, Bibliography, and Index. Oxford University Press, 1982

- Essays in Indian History - Towards a Marxist Perception. Tulika Books, 1995.

- The Economic History of Medieval India: A Survey. Tulika Books, 2001.

- People's History of India - Part 1: Prehistory. Aligarh Historians Society and Tulika Books, 2001.

- People’s History of India Part 2 : The Indus Civilization. Aligarh Historians Society and Tulika Books, 2002.

- A People's History of India Vol. 3 : The Vedic Age. (Co-author Vijay Kumar Thakur) Aligarh Historians Society and Tulika Books, 2003.

- A People's History of India - Vol 4 : Mauryan India. (Co-author Vivekanand Jha) Aligarh Historians Society and Tulika Books, 2004.

- A People's History of India - Vol 28 : Indian Economy, 1858-1914. Aligarh Historians Society and Tulika Books, 2006.

Books Edited

- The Cambridge Economic History of India - Volume I: 1200-1750 (co-editor Tapan Raychaudhari)

- UNESCO History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol 5 : Development in contrast: from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. (Co-editors Chahryar Adle and K M Baikapov)

- UNESCO History of Humanity, Vol 4: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. (With various co-editors).

- UNESCO History of Humanity, Vol 5: From the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. (With various co-editors).

- The Growth of Civilizations in India And Iran

- Sikh History from Persian Sources

- Akbar and His India

- India - Studies in the History of an Idea

- State & Diplomacy under Tipu Sultan

- Confronting Colonialism

- Medieval India - 1

- A World to Win - Essays on the Communist Manifesto (co-editors Aijaz Ahmed and Prakash Karat)

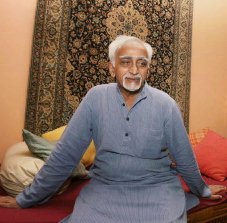

Irfan Habib was born on 12th August, 1931 in Baroda (now Vadodra) Gujrat in a very aristrocrate family of learned scholars. His father Professor Mohammad Habib was a well known historian and a professor in department of history in Aligarh Muslim University.Irfan Habib’s grandfather, Mohammad Naseem was a famous lawyer in Lucknow and a staunch supporter of Aligarh Movement and female education. His mother Sohaila Tayabji was daughter of Abbas Tayabji and grand-daughter of Justice Badruddin Tayabji. Abbas Tyabji was an Indian freedom fighter from Gujarat, who had served as the Chief Justice of the (Baroda) Gujarat High Court. He was son of son of Shamsuddin Tayabji and nephew of Justice Badruddin Tayabji. He was a key ally and supporter of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel during the 1918 Kheda Satyagraha, and the 1928 Bardoli Satyagraha. He was also a close supporter of Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress. In 1919-20, Abbas Tyabji was one of the members of the Committee appointed by the Indian National Congress to review the charges against General Dyer for the Amritsar Massacre, which occurred during the fight for independence from the British. Tyabji became the national leader after leading major protests against the arrest of Mahatma Gandhi in May 1930. He was married to Amina Badruddin Tayabji, daughter of Justice Badruddin Tayabji. Justice Badruddin Tayabji was First Indian to be called to the English Bar (1867), and then the first Indian barrister in Bombay. He entered public life after three years at the Bar. Along with Kashinath Telang and Pherozeshah Mehta, he formed the "Triumvirate" that presided over Bombay's public life. Justice Badruddin Tayabji was President of the 3rd session of the Indian National Congress in 1887 which was held in Madras. He was one of the founders of the Anjuman-i-Islam, his brother Camruddin being President. He was Justice of the Bombay High Court from 1895, acting as Chief Justice in 1902, the first Indian to hold this post in Bombay.

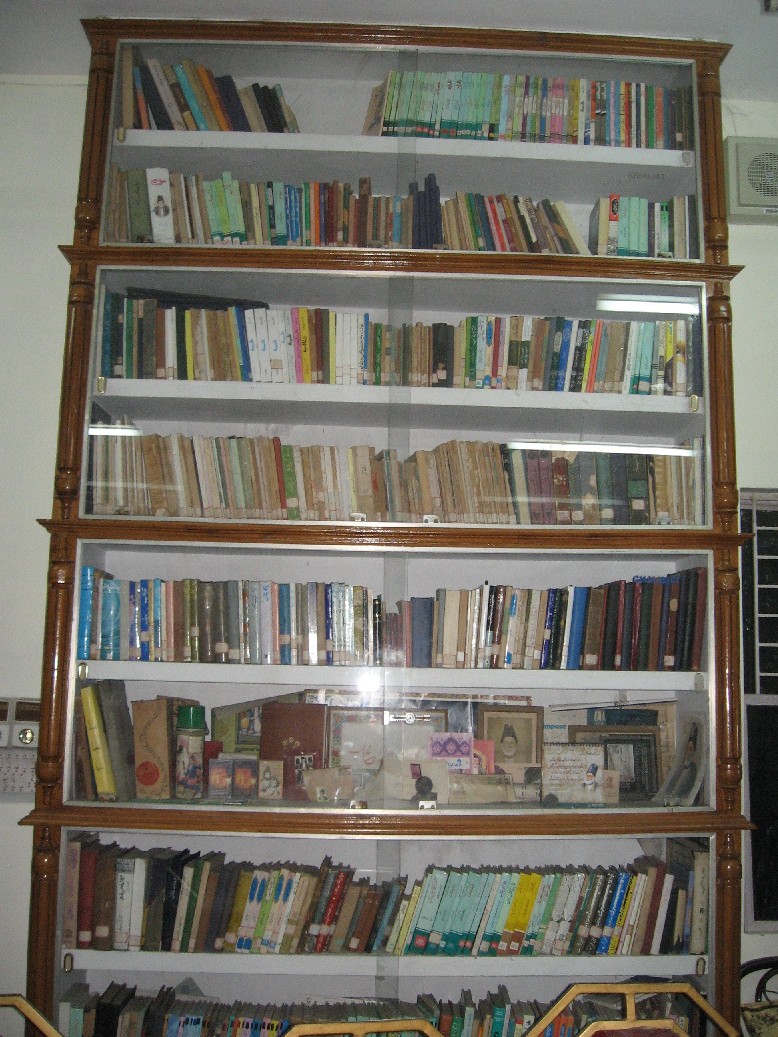

Irfan Habib started his education in Aligarh Muslim University and completed his B.A. in 1951 securing first position and a gold medal and M.A. in History in 1953 with honors and joined as Lecturer in Department of History in Aligarh Muslim University at a very young age of 22 years. He obtained his D.Phil. degree from New College, Oxford. His research “Agrarian System of Mughal India” was well taken by the research community was published in form of a book in 1963. He was appointed as “Reader” in 1960 and “Professor” in 1969 in the Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University. His major publications including, Agrarian System of Mughal India, Essays in Indian History: Towards a Marxist perception and Atlas of the Mughal Empire gave his due place in the academic community. He is also the editor of Peoples History of Indian Series, besides having edited UNESCO publications and Cambridge Economic History of India, Volume I. He has authored and edited number of books, over hundred research papers on various fields of Indian and world history. Prof. Irfan Habib has worked on the historical geography of Ancient India, the history of Indian technology, medieval administrative and economic history, colonialism and its impact on India, and historiography. Amiya Kumar Bagchi describes Habib as "one of the two most prominent Marxist historians of India today and at the same time, one of the greatest living historians of India between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries."

Prof. Irfan Habib had served as Chairman of Department of History of AMU from 1975 to 1977 and from 14th June, 1984 to May 1988. He had also served as Coordinator of Center of Advance Studies (CAS) in Department of History, AMU Aligarh from 1975 to 1977 and 14th June 1994 to 13th May 1996. In 1986, Prof. Irfan Habib was appointed as Chairman of Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) New Delhi, India. He served as its Chairman from 9th September, 1986 to 1st July 1990. He had also served as President and Vice-President of Indian History Congress in 1981 and 2006 respectively. Indian History Congress is India's largest peer body of historians. He delivered Radhakrishnan Lecture at Oxford in 1991. In 1998, he was elected as Corresponding Fellow of British Royal Historical Society, a unique honor earned by his scholarly contribution, recognized by the international community. Prof. Irfan Habib, formally retired on 30.08.1991 has remained associated with the Aligarh Muslim University for all these years without a break, displaying unusual academic interest and scholarly activity that stand out as a model par excellence for every one. Prof. Irfan Habib remains a towering personality fully wedded to the secular values of the Indian Republic. He has illuminated the minds of millions of Indians by his in depth, path breaking erudition of Indian History with a new insight that was so refreshing to the promotion of secular ideals in India. The nation has bestowed on him the coveted civilian title “Padma Bhushan” in 2005. In December 2007, Aligarh Muslim University appointed Prof. Irfan Habib as Professor Emeritus in the department of History. The presence of such a brilliant scholar in the Aligarh Muslim University will add to the academic glory of the institution. He will remain a beacon light for teachers and students of History for several years to come.

A tribute to Irfan Habib: ASHOK MITRA

The Making of History: Essays presented to Irfan Habib edited by K. N. Panikkar, Terence J. Byres and Utsa Patnaik; Tulika

WHY not say it, Irfan Habib is an extraordinary phenomenon. As a historian, he has few peers. His research on The Agrarian System of Mughal India, published in the 1960s, immediately became a classic. Recognition as a fearless exponent of Marxist historiography rained down on him. His initial work pertained to the medieval era of Indian history. He has ceaselessly produced tracts on aspects of this historical period, each of which bears the stamp of his intellectual depth and clarity of writing. His mind and interest did not, however, long stay confined to any particular, narrow phase of events and occurrences. He soon spread out; nothing from the very ancient period to the outer fringes of modern Indian history has escaped his attention. The point has to be emphasised over and over again: whatever he has written has been the product of scholastic endeavour of the highest order: reasoning, primary data not unraveled in the past, application of such data towards formulating credible hypotheses, and the entire corpus built, stone by stone, into a magnificent edifice which can be held in comparison only with other products emanating from Irfan Habib's mind and pen. It is the combination of quantity of output and quality of excellence which has enabled his works reach the reputation of being the other word for supreme excellence.

Inevitably, he has attracted attention as much within the country as outside. Honours have come to him easily. What is of stupendous additional significance, his interpretation of data, building of premises based on such data and expansion of the underlying reasoning, have never strayed away from their Marxist foundation. He has been unabashedly Marxist in his scholastic activities, and has never made a secret of his intellectual and emotional inclination. No run-of-the-mill braggart, his output, every line of it, every expression of his format, has spelled out his faith and belief. Ours is a hide-bound society; it breathes reaction from every pore. Nonetheless, it has been unable to either bypass or be indifferent to Irfan's towering scholarship. Not only has he been accorded the highest academic distinction in an educational institution which has its fair share of retrograde thoughts and demeanour. Even the country's administrative establishment could not fail to take cognisance of his intellectual prowess. Thus the Chairmanship of the Indian Council of Historical Research was offered to him. He held this position for well over a decade, and it was no vacuous adornment of a throne. He used the opportunity to wonderful effect, guiding and counseling historical research at different centres of learning in the country. The result shows in the secular advance in the quality of history teaching and writing in the different Indian universities.

But research interests have not held back Irfan in a narrow mooring. Alongside his individual research activities and the scholastic work he has encouraged around him, his focus of attention has continued to be his students. He has lived for his students , and it would be no exaggeration to claim that he is prepared to die for them. A little facetious research will prove the point: about half of his colleagues on the faculty of history in the Aligarh Muslim University happen to be his former students. It would still be a travesty to infer that he built his students in his own image. He has been a radical thinker, a weather-beaten socialist prepared to combat all ideological challenges, and yet his catholicism as a teacher is by now a legend. Even those whose stream of thought is not in accord with his wave-length have nonetheless found in him the most painstaking teacher who would not deny a student, any student, what he, rightfully or otherwise, can expect of a teacher. Irfan's style of exposition has an elegance of its own: he is an accredited socialist, and yet his command of language, and the manner in which he puts it across, have the hallmark of the legatee of a benign, civilised aristocracy. Maybe in this matter his heredity has been a natural helper.

That does not still tell the entire story of his dazzling career. It is possible to come across scores and scores of arm-chair socialists and radicals whose faith has not nudged them into political activism. From that point of view too, Irfan Habib is al together out of the ordinary. He has been, for nearly three decades, an accredited member of a revolutionary political party; he has not concealed this datum from any quarters. Quite on the contrary, that identity has been his emblem of pride. He has bee n prepared to serve the cause of the party whenever called upon, without however compromising or neglecting his academic responsibilities. It is this blend of intense - if it were not a heresy, one could say, almost religious - belief and fearless participation in political activism which has marked him out in the tepid milieu of Indian academia. His activism, one should add, has widened beyond the humdrum sphere of political speech-making and polemical writing (although, even in his absent-mindedness, his polemics has never descended to the level of empty rhetoric). Irfan's social conscience has prodded him into trade unionism, what many academics would regard as waywardness of the most shocking kind. Irfan could not have cared less for such snobbery. He has also encouraged his students to combine radical thought with political engagement. He has been at the forefront of organisers of teachers' movements. To cap all, he has been the main inspirer and mobiliser of the non-teaching employees of his university and elsewhere. He has suffered on all these accounts including, for a period, suspension from his university. This was an outrage, and social pressure forced the university to revoke its insensate decision.

TO fail to mention his relentless opposition to communal revanchists of all genres will be an unpardonable omission. Muslim fundamentalists have made him their favourite target; of late, Hindu communalists have joined the ranks of this motley crow d. Irfan has not for one moment cowered before this rabble. A quiet, tranquil person in his natural disposition, there is a reservoir of fire in him which has been continuously directed against society's reactionary scum.

For this truly extraordinary scholar, his friends, colleagues and admirers have now assembled, in the form of a festschrift, an extraordinary collection of 23 essays. The Making of History is a labour of love and regard; it is, at the same time, a compendium of much of academic excellence as of social awareness. And it is a magnificently produced volume, for which full credit devolves on the publishers.

THE festschrift opens with a perceptive and comprehensive Introduction covering the major aspects of Irfan Habib's pursuits and fascinations. The essays that follow are arranged in five sections, each of which reflects Irfan's research interests i n different phases. In this brief survey, it is not possible to render justice to each of the different contributions and their authors. The reviewer therefore proposes to draw attention to only some of the essays and seeks forgiveness from the other aut hors.

An additional preliminary comment is perhaps necessary concerning the nature of the contributions: barring one or two exceptions, each essay bears the imprint of a Marxist approach. That is understandable in the light of Irfan's personal inclinations. In that sense, The Making of History is a fusion of subjectivity and objectivity. The contributions include one British, one from Bangladesh and two from Japan.

The first section covers a span of ancient Indian history. Romila Thapar, in her commentary on Rigveda as a mirror of social change, is as incisive and scintillating as ever. She and Suraj Bhan who discusses the Aryanisation of the Indian civilisation, arrive at more or less the same conclusion, Romila a little elliptically and Bhan much more directly: the post-Independence endeavour on the part of some groups to invest Vedic culture superiority over other civilisations of the ancient world constitutes a much overdrawn picture; all that can be said to its credit, or discredit, is that the social stratification which has been the perennial curse of Indian civilisation has its genesis in Vedic times.

The articles in the second section combine analytical rigour and historical insight to explicate the social processes unleashed toward the end of the Mughal period and the accompanying transition of society from the feudal to the semi-feudal mode. Iqtidar Alam Khan traces the antecedents of market formation and narrates the tales of peasant exploitation as well as peasant resistance. Muzaffer Alam and Sanjay Subrahmanyam dig into both archival accounts and contemporary literature. Theories are formulate d in this section on the basis of prior intuitions. These are emended via ferreting of data; new hypotheses thereby rear their head. A charming example is provided by J. Mohan Rao's excursion into production and appropriation relations in Mughal India. I n what is almost an aside, Hiroyuki Kotani discusses rural and urban class structures in the Deccan and Gujarat in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; the piece is both a throwback to ancient times and a preview of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century social complexities.

The third section pushes us into the proximity of the colonial era. The four essays in this section divide themselves into two even groups. The first two papers, by Terence J. Byres and Amiya Kumar Bagchi, are pristine examples of the inter-meshing of economic theory and economic history, with emphasis on building new theoretical constructs. Byres posits an inverse relationship between land productivity and size of holding for Mughal India, basing himself on Irfan Habib's pioneering work and laments the lack of a study, a la Irfan, on the agrarian system of British India. Bagchi's tract on the working class as the historian's burden is breathtaking in its sweep. His premise does not have an altogether specific Indian context; the essay connotes a historicity which has a universal appeal; the endless saga of the repression of the working class and their resistance to it is nonetheless illumined by examples picked from Indian annals, north and south, east and west.

The other two essays in the section are gems of statistical exploration intended to reveal the extent and magnitude of colonial exploitation. Shireen Moosvi painstakingly gathers together data from different sources, adding her own collation of primary data, to establish the empirical truth of the stagnation, and in certain periods, the actual delcine of both per capita income and real wages in the colonial era. On the other hand, Utsa Patnaik wades into the Luxemburgian theme of external exploit ation. Her fresh estimates of eighteenth century British trade as a transfer device from tropical colonies will be quoted, this reviewer has not the least doubt, in future texts attempting to describe the colonial nightmare.

Section four again has a theme-wise bifurcation. The first two essays, the contributions of Javeed Alam and Aijaz Ahmad, constitute a devastating critique of a genre of academic pretensions that have gained prominence in recent years. To be fair, the pro tagonists of such scriptures are often well-meaning in their interpretations. They have, however, been affected by the malady of either left-wing adventurism or straightforward frustration. Both Aijaz Ahmad and Javeed Alam are punctilious in the construction of their hypotheses, and the common conclusion one reaches from assimilating the message of their two essays is that modernity and post-modernism have added at best some footnotes to Marxist historiography. The articles by Mihir Bhattacharya, Ratnab ali Chatterjee and Malini Bhattacharya dwell on the two-way relationship between historical occurrences and the cultural process. Mihir discusses the impact of the grim Bengal famine of the 1940s on the sensitivity of two outstanding Bengali novelists, Manik Bandyopadhyay and Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay. Ratnabali Chatterjee analyses the archaeological evidence of the early traces of nationalism in the cultural nuances of medieval Bengal. Malini Bhattacharya is severe in her attack on the modern-day trends to package so-called ethnic products, including folk songs, musical tunes and handicrafts, for crass commercial purposes. She tells us that the indigenous artists, whatever their sphere of creativity, articulated a deeply felt secularism, from which we should draw inspiration.

Section five ushers in many of the themes of contemporary controversy. K. N. Panikkar analyses the links between culture and nationalism and their anti-thesis represented by communal politics. He does not stray from solid facts, and yet spares no invecti ve for the social reactionaries where such invective is richly deserved. Mushirul Hasan revisits Indian partition. He invites the new generation of historians to cast away the conventional format of Partition studies and concentrate on stressing the hitherto neglected literature on inter-community relations, Partition and national identity. Mushtaq H. Khan sheds light on a problem which has till now scarcely drawn the attention of Indian scholars: what he describes as class, clientelism and communal politics in Bangladesh. K.M. Shrimali's meticulous review of the archaeological evidence pertaining to earlier times has two objectives: first, to question the empirical foundation of the alleged conversion of Hindu religious structures into mosques, et al, in the Muslim epoch, and second, to prove how flimsy is the claim of a Rama temple predating the Babri Masjid in the Ayodhya location.

The final section relates to economics of the modern era. C.P. Chandrasekhar discusses the ongoing economics reforms focussing on the public sector undertakings and suggests that these reflect the construct of a true pompadour non-civilisation. Th e last essay in the volume, by Prabhat Patnaik, is of an altogether different genre. Prabhat depicts his essay as a simple model of an imaginary socialist economy. His modesty is misleading, for his construction is not of an imaginary socialist system, b ut of an idyllic system, which carries forward the Marxist-Leninist ideological postulate beyond Rosa Luxemburg, Oskar Lange and Michal Kalecki. Prabhat's conceptual model of an internally consistent socialist economy, this reviewer is firmly of the view, will still the disquiet of many doubting Thomases.

The volume ends with a detailed and conscientious list of Irfan's publications, which will be of immense use to future research scholars.

All told, The Making of History is a most appropriate tribute to Irfan Habib's unrelenting commitment to history and the social sciences. Several of the contributions in the volume, one is tempted to suggest, are bound to make history!

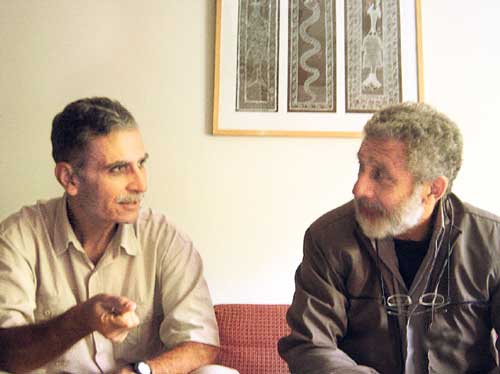

January 5, 2001: The Rediff Interview/ Professor Irfan Habib

The saffronisation of Indian history has been a controversial subject ever since the Bharatiya Janata Party assumed power at the Centre. This has angered many leading historians in the country.

The apprehension of historians like Professor Irfan Habib arises from the fact that this process will result in a distorted interpretation of Indian history.

In Calcutta to attend the 61st session of the Indian History Congress, Professor Habib, a former head of the Indian Council of Historical Research, spoke to Rifat Jawaid about the revival of the Babri Masjid controversy and other issues pertaining to Indian history.

The 61st session of the Indian History Congress is being held at a time when the Babri Masjid issue is once again being debated. What does the IHC make about the revival of the Ayodhya controversy?

It's not historical evidence that is being talked about today. The position of the Indian History Congress in the past was that irrespective of the origin of the Babri Masjid, the structure should not have been demolished. Whether those who said there was a Ram temple underneath and those who said there wasn't -- the point is that once a structure is established and it becomes an ancient monument, it can't be disturbed. These two controversies must be absolutely delinked.

Therefore, in the Warangal Resolution of March 1993, the History Congress specifically criticised the Government of India for referring the matter to the Supreme Court. We have maintained all along that the structure that upholds must be preserved as it is.

The only thing which has revived the controversy is Vajpayee's assertion that the destruction of the Babri Masjid was a kind of a national movement. So obviously, historians are perturbed with the prime minister's interpretation of what was an act of vandalism.

An ICHR offical recently stated that there was no Babri Mosque at the disputed site in Ayodhya. How do you react to his statement?

Sushil Kumar, the person whom you are referring to, is merely a director of the Indian Council of Historical Research. He is not a historian. By making such statements, he probably feels he could please his masters.

Do you think people without a background in history should be allowed to hold key positions in an organisation like the ICHR?

Ask this question to the present regime.

How do you compare the National Democratic Alliance government with its predecessors?

Other regimes were not interested in a particular ideological myth. The present regime wants to impose a specific mindset or ideology which is not an ideology of science. This is how I find the present government different from the regimes we had in the past.

As a historian, how disturbed are you by the reported attempts of the saffronisation of Indian history? There are reports that saffronisation is taking place in text books, educational institutions such as the ICHR, the Indian Council of Social Sciences Research and the National Council for Education, Research and Training.

You are asking me two different questions. First, we must understand what value education the HRD ministry in the BJP government is talking about. To me, value education is another name for religious instructions as it is clear from the curriculum and filling up of posts in the NCERT with those practicing the ideology of the Sangh Parivar. But that is declared illegal by the Indian Constitution. By our Constitution, no State-supported institutions can impart religious instructions on a compulsory basis. It is unconstitutional.

The BJP government is visibly concerned because religious instructions mean, to that extent, a scientific approach is automatically curtailed. Be it Islam or any other religion, the very nature of religion is that you accept it. No archaeologist worth his name can say that Ibrahim founded the Kaaba, yet Muslims believe this. So clearly, religion must be separated.

Secondly, history deals with religious beliefs that the Kaaba was founded by Ibrahim. Therefore, I believe religion does not prove its beliefs by history and history does not accept the fact of the religion unless of this kind. If these two issues are mixed in Indian education, it will mark the demise of scientific and rationale education in the country.

How difficult is it for independent researchers to carry on with their work under the BJP government? Not so long ago, two historians -- Sumit Sarkar and K N Panikkar -- had alleged that two of their volumes on the freedom movement were withdrawn because they refused to toe the Sangh Parivar line.

So long as India continues to uphold the dignity of democracy and civil rights, there is no reason why historians should feel intimidated. As for the withdrawal of the two volumes edited by two eminent historians, I feel it is a matter for the ICHR. The Indian History Congress has that matter on its agenda and we will get a resolution on it during our three-day conclave. The general body of our Congress will debate this issue extensively.

The BJP government is being singled out for recruiting scholars who toe their line. But the Left Front government in Bengal has often been accused of appointing people with a Marxist background to sensitive positions. As a Marxist, how can you justify this?

Even I have come across such reports in a section of media. As for Bengal, all the appointees here were never been short of basic prerequisites. They have always fulfilled the academic standards. The only difference between the BJP government and the non-BJP ruled states including Bengal is that the latter did not regard Marxist views as totally unacceptable.

History is based on fact. Yet one often sees historians divided on any given issue. Many people say personal prejudice and political lineage influence researchers.

Every individual sees a particular set of historical facts differently. It may be because of his experience, affiliation and political allegiance. However, there is very little doubt that they are all historians. On the other hand, the kind of things the Sangh Parivar is busy doing today? It is not adhering to any historical facts.

A true historian can never say anything outside the framework of historical facts. The only satisfying revelation is that those who believe in distorting

facts. The only satisfying revelation is that those who believe in distorting history are very few in number. There are many who owe political allegiance, but they do not necessarily follow them while researching certain subjects.

Coming back to the Babri Masjid controversy, what is your personal reading? Was there really a Ram temple on which Babar constructed a mosque?

I have no different opinion than what some eminent historians have already said on this issue. Actually, this historical evidence was collected and a detailed report issued by four historians of repute in the past. They observed that when the Babri Masjid was being constructed, there was no memory of a Hindu temple in Avadh, which was then a medieval town.

===========================================================

The nation that is India: Prof. Irfan Habib

The article was published in The Little Magazine.

When Benedict Anderson published his Imagined Communities in 1983, with the subtitle Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism, the text was widely hailed as an unanswerable critique of the claims to nationhood by peoples outside Western Europe. Very few readers of Anderson apparently had the patience to reflect that too much was perhaps being read in the new word ‘imagined’. Earlier writers had used words like ‘consciousness’, ‘belief’, ‘consider’ (the last in Seton-Watson, quoted by Anderson himself), to indicate that a nation comes into existence when large numbers become convinced that they form one. But in this respect, the nation is no different from any other ‘community’ or association, whether a religious community or family or tribe or caste or even profession. It is only in our ‘imagination’ that a fellowship in faith, or a common ancestry, or a similar way of doing things makes us see some of us as a community or a class. Indeed, it is our ‘imagination’ that makes us so different from animals.

If there is a point in Anderson’s book, of which a reminder would be useful, it is that consciousness of nationhood is of comparative recent origin: for the world at large, outside Western Europe, it is mainly a post-French Revolution (1789) phenomenon. But this was not, unlike what Anderson tells us, simply because the exciting ideas of the French Revolution first caught the imagination of ambitious individuals in Latin America, starting with Simon Bolivar. The crucial basis for emerging nationhood was provided by colonialism, which was no imagined phenomenon either for Latin America, or for Asia and Africa. Colonialism was ruthlessly exploitative, and it could be opposed only if people, who were oppressed, were brought together on the largest scale possible. The ‘nation’ provided precisely such a unifying platform.

Colonialism was also an unconscious agency for a momentous transfer of ideas. Based in Europe (and the United States), its economic framework rested on the capitalist economy of the metropolitan countries. It was necessary for colonialism itself that parts of capitalist infrastructure, such as railways, processing factories, and some technology, should reach the colonies; and that certain numbers of colonial populations should learn the languages of the rulers for convenience of governance. These steps opened the doors to the transmission of ideas and knowledge from Europe. Marx described this as a source of ‘regeneration’ of the exploited people (he was speaking in 1853 with reference to India), in contrast to the ‘destructive’ role that colonialism had simultaneously played in the sphere of economy and society of the colonial peoples.

This notion of a dual process of destruction and regeneration was challenged by Edward Said in his Orientalism, the first edition of which came out in 1978. Despite his disclaimers in the ‘Afterword’ appended to the 1995 edition, Said clearly argues in his main text that European studies of eastern countries and peoples fundamentally distorted the pictures of the latter’s true cultures. Soon, one began to hear of ‘colonial discourse’ and even ‘colonial knowledge.’ In Imagining India, first published in 1990, Ronald Inden asserted that "the agency of Indians, the capacity of Indians to make their world, has been displaced in these [Orientalist] knowledges (the plural shows that we are now in the framework of post-modernist ‘knowledge’ on to other agents." Edward Said concedes in his Afterword that he did not wish to deny the ‘technical’ achievements of the ‘Orientalists.’ He should, however, have paused to examine what these technical aspects amount to. In essence, these flow from the assumption that non-European peoples can be studied by the same methods and criteria as the European. The concept of the ‘other’, the initial point of colonial discourse, was thus continuously undermined by the universality of the scientific method that the Orientalist needed to be committed to. That is often why the prejudices and aberrations of one generation of Orientalists were exposed and rejected by the next.

It is in fact the concept of universality that is of particular importance in the transmission of ideas from the West to the East. ‘Liberty’, ‘Constitution’ and ‘Nation’ were not just principles suited to Europe, but were applicable, under similar circumstances, to all of mankind. Countries in the East could also, therefore, become ‘nations’. When Raja Rammohun Roy, in an 1830 letter, asserted that India was not a nation because Indians were "divided up among castes," he implicitly accepted that India could become a nation if its people shifted their primary loyalties from caste to country. In 1870, Keshav Chandra Sen was already looking forward to this prospect in the light of India’s educational development and social reform. By the very name that the moderate Indian leaders gave to the organisation they founded at Bombay in 1885 — the Indian National Congress — the proposition that India is a nation was widely proclaimed.

But why was India chosen as the nation, and not individual territorial divisions within it? Perhaps it was because India alone was seen as a country. Several nations have been created, such as the United States, Ecuador, Bolivia or Congo, which had no previous existence as countries; but such instances belong to areas where for one reason or another there was no preceding accepted concept of country. Where such concepts have existed since pre-modern times, the country already existing in the popular mind becomes a natural candidate for nationhood. It is clearly for this reason that Ba’athist or Nasserite Arab nationalism has found it so difficult to replace the separate nations of Egypt, Syria and Iraq with one, single, indivisible ‘Arab nation’. The existence of India as a country had long preceded British rule. It was due undoubtedly in part to facts of geography, with the Indian peninsula separated by mountains and the sea from the Eurasian continent. Within the limits so set, cultural affinities had developed which led people to distinguish those in India from the rest of the world. Many of these affinities appear as aspects of the Hindu tradition. That the caste system and Brahmanical ideas and rituals were important among the culturally shared elements is undeniable. But it can be shown (as I have tried to do in a couple of essays) that the concept of India as a country is stronger in writers like Amir Khusrau (d.1325) or Abu’l Fazl (d.1603), writing in Persian, than in any identifiable preceding writer in Sanskrit. This is surely because the cultural affinities were not exclusively religious. Tara Chand, in his Influence of Islam on Indian Culture, observed that extensive political structures like the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire helped to generate larger political allegiances, and so made the consciousness of the country’s unity still stronger. Even in the eighteenth century, when he had lost all power, the Mughal emperor was seen as the natural sovereign of Hindustan. And when the rebels of Avadh, in the name of Prince Birjis Qadr, penned their defiant reply to Queen Victoria’s Proclamation of 1858, they spoke of the wrongs that the British had done to the princes of Hindustan, referring to both Tipu Sultan of Mysore and Maharaja Dalip Singh of the Punjab. In their words, it was "the army and people of Hindustan" that had now stood up to challenge the British. The 1857 rebels thus saw India very clearly as their country, and their natural reserve of supporters. If the India of their perception was still not a nation, it was only because they did not yet have any notion of establishing a single state over the country — and a unified political entity is the crux of nationhood.

The unification of the country on an economic plane by the construction of railways and the introduction of the telegraph in the latter half of the nineteenth century, undertaken for its own benefit by the colonial regime, and the centralisation of the administration which the new modes of communications and transport made possible, played their part in making Indians view India as a prospective single political entity. Modern education (undertaken in a large part by indigenous effort) and the rise of the press disseminated the ideas of India’s nationhood and the need for constitutional reform. A substantive basis for India’s nationhood was laid when nationalists like Dadabhoy Naoroji (Poverty and UnBritish Rule in India, 1901) and R.C. Dutt (Economic History of India, 2 vols., 1901 and 1903) raised the issues of poverty of the Indian people and the burden of colonial exploitation, which was felt in equal measure throughout India.

We see, then, that three complex processes enmeshed to bring about the emergence of India as a nation: the preceding notion of India as a country, the influx of modern political ideas, and the struggle against colonialism. The last was decisive: the creation of the Indian nation can well be said to be one major achievement of the national movement.

The idea once propounded had to be defended against numerous critics. The Simon Commission Report (1930) pointed to India’s cultural diversities, its religious divisions and the multiplicity of its languages. One could retort by citing the classic example of Switzerland, a land of Catholics and Protestants and four languages. But beyond these technical quibbles was the stake that the people could be persuaded to see in a unified, free India. The real answer to the Simon Commission was, therefore, the Karachi Resolution of March 1931, in which the Congress spelt out the political, social and economic contours of the future free India in which the state would ensure ‘fundamental rights’ to all. The Indian state, it was pledged, would observe ‘neutrality in regard to all religions’, and the cultures and languages of ‘the different linguistic areas’ would be protected.

Religious divisions undoubtedly undermined this notion of a secular, single nation of India. That a divide-and-rule policy was of advantage to colonialism may be taken for granted. Such a policy could not, however, succeed if the seeds for division did not exist. The same new conditions, notably the rapid means of communications and the press, which had so helped the nationalist cause, also provided platforms for communalist propaganda, both Hindu and Muslim, on a scale and of a type no one could have imagined in the pre-1857 period. In the earlier stages, one strand of nationalism also played with religion: it could supply a source of mass mobilisation when other instruments were lacking. Tilak’s agitations in the 1890s against the Age of Consent Bill and plague inoculation, together with his espousal of the Shivaji cult, offer classic illustrations of this tendency. Aurobindo Ghosh provided simultaneously the theoretical basis for a ‘Hindu Nationalism’. Tilak’s senior contemporary Jamaluddin Afghani similarly propounded the doctrine of pan-Islamism to unite all Muslim peoples against European colonial powers — the unifying factor was again religion. Afghani’s exclusion of India from his scheme did not mean that the vision once propounded would not exert any influence on Indian Muslim minds.